What is maritime boundary?

- A maritime boundary is a conceptual division of the Earth's water surface areas using physiographic or geopolitical criteria.

What is maritime dispute?

- Maritime boundary dispute is a dispute relating to demarcation of the different maritime zones between or among states.

- A maritime boundary is a conceptual division of the Earth's water surface areas using physiographic or geopolitical criteria.

What is maritime dispute?

- Maritime boundary dispute is a dispute relating to demarcation of the different maritime zones between or among states.

Background

A maritime boundary is a conceptual division of the Earth's water surface areas using physiographic and/or geopolitical criteria. As such, it usually includes areas of exclusive national rights over mineral and biological resources, encompassing maritime features, limits and zones. The oceans are without doubt the most important resources on the planet and only maritime states can boast of their fortune, having economic, political, strategic and social advantages over other states in reaping benefit from those resources while their interests are manifest in a variety of activities including shipping of goods, fishing, hydrocarbon and mineral extraction, naval mission and scientific research. Bangladesh is, too, bestowed with the same geographic endowment with 720-kilometre coastline. However, questions remain whether the country has been successful in valorizing the magnitude of its maritime interests so as to establish its rights as a maritime state in the Bay of Bengal and pursuing a process conducive to fruitful resolution of the wrangles with its neighbors.

Bangladesh’s Law for Maritime Zones

In Pursuant to Article 143(3) of the Constitution, Bangladesh enacted laws, Territorial Waters & Maritime zones Act on 14 February, 1974i, with regard to the law of the sea in the Bay of Bengal while ratifying 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS-III) in 2001.The coastal marine areas of Bangladesh in the Bay of Bengal are divided into three zones under the (UNCLOS-III) territorial waters of 12 nautical miles, another 200nm of EEZ and 350 nm of sea bed, continental shelf from Bangladesh baseline. For the unique deltaic characteristics of its coast, Bangladesh determined the baseline in 1974 with a length of 222 nm which is 8 points fixed at 10 fathoms (60ft) extending to 10-30 miles from the coastline. However, the total sea area of Bangladesh in accordance with the UNCLOS-III is approximately 2, 07,000 square kilometers, 1.4 times greater than its total land area.

Fig: Bangladesh's Law for maritime Zones

History of the Boundary dispute

Following negotiations between Bangladesh and Myanmar, in 1974, the two countries reached an understanding regarding the delimitation of their respective territorial seas to a distance of 12 nautical miles from their coastlines. As per the terms of the 1974 Agreed Minutes, signed by delegations of the two countries, Bangladesh permitted Myanmar's vessels free and unimpeded navigation through Bangladesh's waters around St. Martin's Island to and from the Naaf River.

However, despite extensive negotiations for over three decades, since 1974, the two neighbours had been unable to agree on the delimitation of the boundary in the Exclusive Economic Zone and the continental shelf. Bangladesh has divided the area EEZ into 28 blocks for exploring gas and oil. When the plane was going to be implemented, Myanmar & India disputed claiming the ownership of at least 10 & 8 blocks in the Bay-of-Bengal.

Upon assuming office in early 2008 the Awami League government engaged in further negotiations with the government of Myanmar. However, from 2008 onwards, Myanmar started denying the existence of any formal agreement between the parties regarding maritime delimitation.

Having failed to resolve the issues bilaterally the Bangladesh government took the bold decision on December 13, 2009, to initiate arbitration pursuant to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to secure the full and satisfactory delimitation of Bangladesh's maritime boundaries with Myanmar in the territorial sea, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf in accordance with international law.

Myanmar's position had always been that the delimitation of the territorial sea on the one hand and the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf on the other hand, had to be settled together. There were also conflicting and overlapping claims to the outer continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles, with each state claiming that the outer shelf is the natural prolongation of its own landmass, and the other state has no rights to the outer continental shelf.

Myanmar had insisted that the maritime boundary should be delimited on the basis of "equidistance." Bangladesh had always wanted a solution to the issue based on "equitable principles/relevant circumstances rule." If the "equidistance principle" was used to draw the maritime boundary this would have resulted in the drawing of a median line equidistant from the shores of Bangladesh and Myanmar. However, given the unique concavity of the Bangladesh coastline an equidistant line would have deprived Bangladesh a substantial portion of the seas. Thus, Bangladesh wanted the maritime boundary to be drawn using the "equitable principles" rule under which a provisionally drawn equidistance line is adjusted (or abandoned) in consideration of the "special" or "relevant" circumstances. The unique concavity of the Bangladesh coastline would be one of these "special" or "relevant" circumstances.

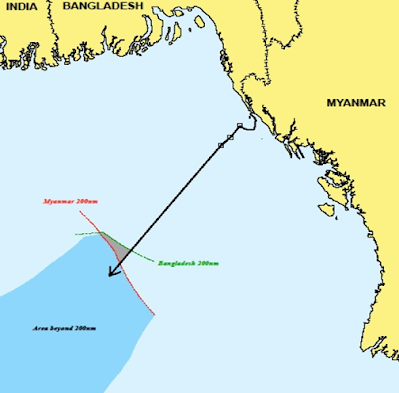

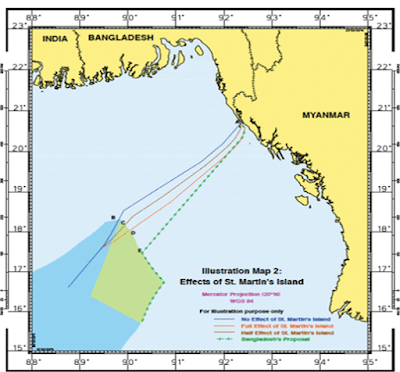

Fig: The Maritime Zones with Conflicting Claims

Delimitation within & beyond 200 nautical miles

The tribunal first noted that in drawing the maritime delimitation the goal of achieving an equitable result was of the paramount consideration. It thus adopted the "equidistance/relevant circumstances" method preferred by Bangladesh. The tribunal observed that the coast of Bangladesh was manifestly concave and since the equidistance line produces a "cut-off" effect on the maritime entitlement of Bangladesh an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line was necessary to reach an equitable result. It adjusted the provisional equidistance line to reach an equitable solution taking into account the relevant circumstances, notably the concavity of the Bangladesh coastline.

Regarding the outer continental shelf areas, states can potentially lay claim to areas more than 200 nautical miles from their coastlines if they can prove that the seafloor in that area possesses one of two characteristics:

(i) a certain thickness of sedimentary rocks, or

(ii) the existence of certain morphological/topographic features.

If a coastal state can demonstrate the existence of one of these two characteristics, it must make a submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). Myanmar argued that since neither it nor Bangladesh had established the outer limit of the continental shelf based on recommendations from the CLCS, delimitation of that area by the Tribunal would be nothing more than a hypothetical exercise, as it did now know what the outer limits would be.

It also argued that it would not be appropriate for International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) to exercise jurisdiction over the outer continental shelf since this would prejudice the rights of a third party, implying India, which also has claims in the outer continental shelf areas.

Bangladesh stressed the point that UNCLOS does not prevent the tribunal from exercising jurisdiction over areas beyond 200 nautical miles. Bangladesh also argued that potential claims of third party states cannot deprive ITLOS of its jurisdiction since third parties are not bound by the judgment of ITLOS and its rights are thus unaffected by the judgment. Bangladesh pointed out that there was no conflict between the roles of ITLOS and CLCS. It argued that their roles are complementary because the CLCS's rules prevent it from issuing recommendations on the outer limits of the continental shelf when there is a dispute concerning delimitation. Thus, the recommendations of the CLCS were not a prerequisite to the jurisdiction of ITLOS, as was being argued by Myanmar.

The tribunal agreed with Bangladesh and found it had jurisdiction to delimit the continental shelf in its entirety. It noted that its exercise of its jurisdiction to delimit the outer shelf did not encroach on the functions of the CLCS. The tribunal determined the direction of the maritime boundary without indication a precise terminus, specifying instead that the maritime boundary line continued until the rights of a third party are affected. After reaching the end of the exclusive economic zone the line continues at the same bearing into the outer continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles. The exercise of jurisdiction by ITLOS to delimit the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles is the most significant legal aspect of the judgment. This was for the first time that a tribunal exercised jurisdiction to delimit a maritime boundary in the outer continental.

Fig: International Tribunal Final Delimitation of Territorial Sea

Fig: Tribunal Delimited “grey area” in which Bangladesh has jurisdiction over the seabed but Myanmar’s has jurisdiction over the water.

Significant gains for Bangladesh in the maritime boundary dispute with Myanmar & India

Shortly after the judgement, the Foreign Minister(2012) of Bangladesh, Dipu Moni, hailed the gains achieved by Bangladesh through the resolution of the long-standing maritime dispute between Bangladesh and Myanmar. She stated that all of our strategic objectives were achieved. The foreign minister continued: "Bangladesh's full access to the high seas out to 200 nautical miles and beyond is now recognized and guaranteed, as are our undisputed rights to the fish in our waters and the natural resources beneath our seabed. Bangladesh claimed 107,000 square kilometers while it got 111,000 square kilometers area in the Bay of Bengal. Bangladesh has also won another maritime boundary dispute with India after the last one with Myanmar. The Permanent Court of Arbitration at Hague in Netherlands has awarded Bangladesh 19,467 square-kilometers out of total 25,602 square-kilometers disputed area with India in the Bay of Bengal.

Much credit goes to the government of Bangladesh for handling this case with due diligence and giving it the focused attention, it deserved. The foreign minister herself led the Bangladesh team from the front opening the submissions for Bangladesh. She was assisted by the equally capable and knowledgeable Rear Admiral (Retd) Md. Khurshed Alam. Bangladesh was ably represented by a "dream team" of international lawyers .The immediate impact of the judgment of March 14 is that Bangladesh will be able to carry out exploration for oil and gas in several offshore blocks that show enormous potential.

Conclusion

The 14th March 2012 ITLOS judgement and the Arbitration Award of July 07, 2014 is significant for both Myanmar, Bangladesh & India. It is a peaceful resolution that allows both countries to begin exploration and infrastructure development necessary for the extraction of potentially highly profitable hydrocarbon gas reserves in the Bay of Bengal. Both sides are claiming victory in the dispute.

The ITLOS Judgment and the Arbitration Award have provided to the people of Bangladesh a just and equitable share of the maritime resources of the Bay of Bengal. The Government’s courageous and visionary decision, against two larger neighbors has helped break the 40-year severe and arbitrary limitations on maritime access.

The final determination of the maritime boundaries of Bangladesh will be of immense benefit to the 160 million people of Bangladesh in as much as Bangladesh would be able to explore, in an unhindered manner, the possibilities for oil and gas exploration. The advancement of technology over the last few decades has meant that the exploitation of submarine petroleum and mineral resources has become commercially viable.

Given the growing scarcity of energy, and the high potential of discovery of gas and petroleum resources in the Bay of Bengal, the favorable decisions obtained by Bangladesh could prove to be of significant economic value. It would be very good for Bangladesh if we, as a people, could be united in our appreciation of these positive results for Bangladesh.

Tags: a great victory, boundary map, bay of bengal dispute Bangladesh - Myanmar