1. Mercantilism is a bankrupt theory that has no place in the modern world. Discuss.

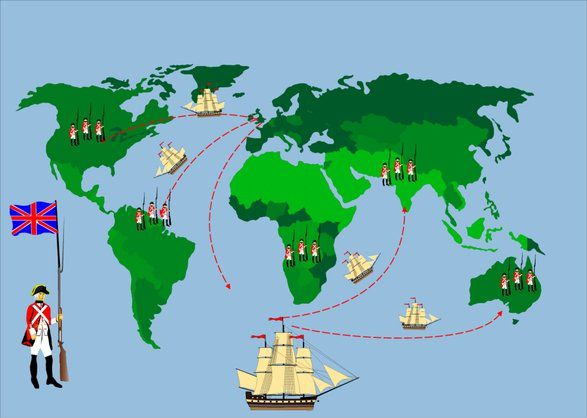

Mercantilism, in its purest sense, is a bankrupt theory that has no place in the modern world. The principle tenant of mercantilism is that a country should maintain a trade surplus, even if that means that imports are limited by government intervention. This policy is bankrupt for at least two reasons. First, it is inconsistent with the general notion of globalization, which is becoming more and more prevalent in the world. A policy of mercantilism will anger potential trade partners because it will exclude their goods from free access to the mercantilist country’s markets. Eventually, a country will find it difficult to export if it imposes oppressive quotas and tariffs on its imports. Second, mercantilism is bankrupt because it hurts the consumers in the mercantilist country. By denying its consumers access to either “cheaper” goods from other countries or more “sophisticated” goods from other countries, the mercantilist country’s ordinary consumers suffer.

2. Is free trade fair? Discuss!

The specialization and free trade benefits all countries. However, a case can be made in some situations for imposing trade barriers. For example, if a developing country is trying to establish an industry, trade barriers may be needed in the short term until the industry can become competitive.. It could be argued that another country could make the product more efficiently already, is it fair to limit a country’s ability to develop its industrial base.

3. Unions in developed nations often oppose imports from low-wage countries and advocate trade barriers to protect jobs from what they often characterize as "unfair" import competition. Is such competition "unfair"? Do you think that this argument is in the best interests of (a) the unions, (b) the people they represent, and/or (c) the country as a whole?

The theory of comparative advantage postulates that a country should specialize in producing those goods that it can produce most efficiently, while buying goods that it can produce relatively less efficiently from other countries. The theory suggests that opening a country to free trade stimulates economic growth, which creates dynamic gains from trade. Therefore, it would follow that if low-wage countries can make certain products more efficiently than high wage countries, the low wage countries should produce and export those products. While trade barriers may protect workers and companies, they are a short-term fix at best. Moreover, by protecting industries, the government is not encouraging companies to become more efficient. Instead, they are promoting inefficiency. Consumers lose out because they have higher prices and less choice.

4. What are the potential costs of adopting a free trade regime? Do you think governments should do anything to reduce these costs? What?

Some will recognize that by adopting a free trade regime, jobs will be lost in some industries, however they may not agree on exactly what should be done about the jobs losses. Someone might suggest that the government provide retraining programs while others may argue that people lose their jobs everyday and don’t get government assistance to find new ones.

5. Reread the Country Focus "Is China a Neo-mercantilist Nation?"

a) Do you think China is pursuing an economic policy that can be characterized as neo-mercantilist?

b) What should the United States, and other countries, do about this?

Yes. China has embraced economic mercantilism on an unprecedented scale, using a wide array of policies to assist Chinese firms while discriminating against foreign establishments attempting to compete in China. Hence it can be argued that China.

The economic strength of the United States, however, provided the stability that permitted the world to emerge from the postwar chaos into a new era of prosperity and growth. The Marshall Plan provided American resources that overcame the most acute dollar shortages. The Bretton Woods agreement established a new system of relatively stable exchange rates that encouraged the free flow of goods and capital. Finally, the signing of the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) in 1947 marked the official recognition of the need to establish an international order of multilateral free trade.

The mercantilist era has passed. Modern economists accept Adam Smith’s insight that free trade leads to international specialization of labor and, usually, to greater economic well-being for all nations. But some mercantilist policies continue to exist. Indeed, the surge of protectionist sentiment that began with the oil crisis in the mid-1970s and expanded with the global recession of the early 1980s has led some economists to label the modern pro-export, anti-import attitude “neomercantilism.” Since the GATT went into effect in 1948, eight rounds of multilateral trade negotiations have resulted in a significant liberalization of trade in manufactured goods, the signing of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) in 1994, and the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) to enforce the agreed-on rules of international trade. Yet numerous exceptions exist, giving rise to discriminatory antidumping actions, countervailing duties, and emergency safeguard measures when imports suddenly threaten to disrupt or “unfairly” compete with a domestic industry. Agricultural trade is still heavily protected by quotas, subsidies, and tariffs, and is a key topic on the agenda of the ninth (Doha) round of negotiations. And cabotage laws, such as the U.S. Jones Act, enacted in 1920 and successfully defended against liberalizing reform in the 1990s, are the modern counterpart of England’s Navigation Laws. The Jones Act requires all ships carrying cargo between U.S. ports to be U.S. built, owned, and documented.